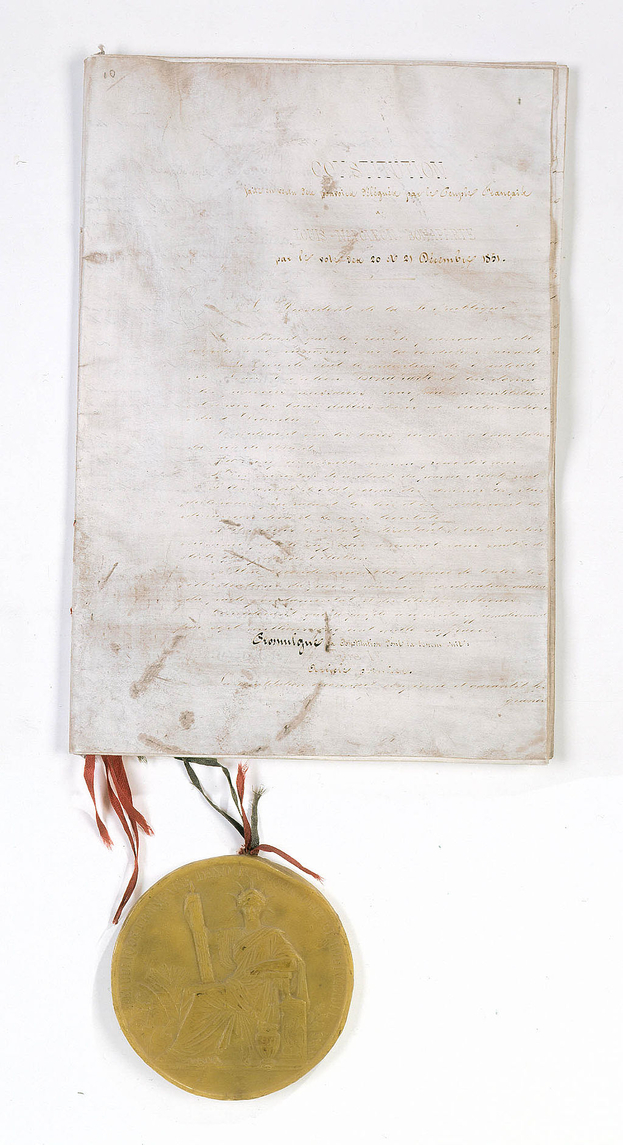

The result of a coup d’État, the Constitution of 14 January 1852 replaced the Constitution of 4 November 1848 as the founding text of the Second Republic. Promulgated by President Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, it was modified by the sénatus-consulte of 7 November 1852 to become the Constitution of the Second Empire.

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, was elected president in December 1848, for four years, non-renewable. On 2 December 1851, the anniversary of Napoleon's coronation and the victory at Austerlitz, he launched a military coup d’État, intended to retain his power, which the French people, called to vote, approved by 92%, granting him total freedom to draft a new constitution.

From its first article, the Constitution of 1852 rejected the model of constitutional monarchies by redeeming the key principles of 1789, which it recognized as the basis of French public law. While this affirmation showed a will to reject constitutional monarchies, the articles that followed described a return to a quasi-monarchist conception of the head of State, by granting him extensive powers.

Elected for ten years, the President of the Republic not only had the right to declare war and sign treaties, but could also appoint all functions and choose the ministers.

The independence of the legislative power was reduced, and the President was responsible for initiating legislative acts, which the deputies could not amend, no more than they could control the ministers’ actions. This parliament was made up of a legislative body, with 250 deputies elected every six years, and a Senate, made up of ex officio members, such as marshals, admirals and cardinals, and members appointed for life by the President, to resolve by sénatus-consulte anything which was not provided for in the Constitution.

This vast personal power was nonetheless built on the concept of popular sovereignty, through frequent use of plebiscites: the head of State “may at any time call on sovereign judgment [of the French people] so that, in solemn circumstances, [they may] continue or withdraw [their] trust”.

True to this principle, he summoned the opinion of the French people in November 1852, for their approval to re-establish imperial dignity. The result was a landslide in favour of yes, with 824,189 for and 253,145 against.

Less than one year later, a sénatus-consulte re-established imperial dignity: the political structure of 1851 was preserved, but the President of the Republic elected for ten years changed to a life-long Emperor.

Updated : 15 December 2022