On 13 October 1946, after many lively and lengthy discussions, the French people approved by referendum the constitution of the Fourth Republic. Two constituent assemblies, two draft constitutions and three referendums were needed to equip France with new institutions following the Liberation. Criticized even before it was introduced by General de Gaulle in his famous Bayeux speech on 16 June 1946, the Fourth Republic was built on fragile foundations: there were high numbers of protest votes and abstention, so high that the yes vote actually represented just 36% of registered voters.

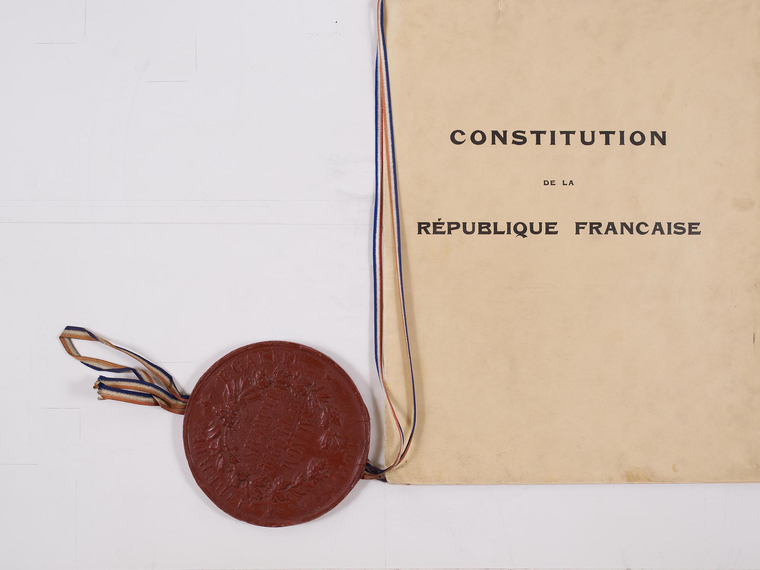

Promulgated on 27 October 1946, the Constitution of the Fourth Republic included a preamble followed by 106 articles, in the tradition of the revolutionary constitutions of 1791, 1793, 1795 and 1848.

Solemnly affirming the restoration of democracy after the “parenthesis” of the French State (1940-1944), the preamble was in keeping with the 1789 tradition and introduced new principles, namely economic and social ones: equality in all areas for men and women; the right to asylum for all those persecuted for their actions in support of freedom; the right to work; the right to join a union; the right to strike; the right of workers to participate in the management of companies; the right of the State to nationalize any company with a de-facto monopoly; and the right to education and leisure activities. These affirmations meant that a series of decisions taken since the Liberation could be legalized: nationalizations, women's suffrage, workers’ councils, social security, etc. The preamble also established a French Union between France and its overseas peoples, formerly colonized by France.

The 106 articles in the text established an assembly regime. While it provided for a second house, the Council of the Republic, which replaced the Senate, the Constitution granted the majority of the legislative power to the “National Assembly”, the name of which was taken from the 1789 and 1848 revolutions, replacing the “Chamber of Deputies” under the Third Republic. Elected for five years, it alone voted on acts of parliament, while the Council could merely issue an opinion. The National Assembly elected, with the Council of the Republic, the President of the Republic, and voted, through absolute majority, on the inauguration of the President of the Council, appointed by the President to lead the government. Lastly, it had permanent control over the government’s action. As the President's powers were limited, the National Assembly exercised supremacy in the balance of powers.

Reviewed in 1954 on minor points, the constitution was dismissed in 1958, in the context of the war in Algeria. On 1 June, the National Assembly inaugurated Charles de Gaulle as President of the Council and on 3 June, authorized him to draw up a draft constitution to be submitted directly to referendum: the Fourth Republic was dead, and the Fifth was born.

It is customary to attribute the ministerial instability of the Fourth Republic to the Constitution of 1946. In reality, the causes were external. The first was due to the adoption of election by proportional representation based on lists, which made it possible for more small parties to sit in the Assembly and prevented the formation of stable majorities. The second was due to a practice that was not foreseen in the Constitution, and was introduced by the President of the Council Paul Ramadier. Ramadier submitted the composition of his government to inauguration by the Assembly, establishing a dual inauguration that limited the executive's latitude.

Furthermore, while the Fourth Republic proved to be powerless in solving the Algerian crisis, it ensured the State's action continued to be implemented, thanks to the stability of the politicians and the monitoring of public policies by high-ranking civil servants. It laid the groundwork for the modernization of France, granted independence to Tunisia and Morocco and autonomy to the sub-Saharan African colonies in 1956, and started work on European integration by creating the ECSC in 1951 and signing the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

Preamble to the Constitution of October 27th 1946

In the morrow of the victory achieved by the free peoples over the regimes that had sought to enslave and degrade humanity, the people of France proclaim anew that each human being, without distinction of race, religion or creed, possesses sacred and inalienable rights. They solemnly reaffirm the rights and freedoms of man and the citizen enshrined in the Declaration of Rights of 1789 and the fundamental principles acknowledged in the laws of the Republic.

They further proclaim, as being especially necessary to our times, the political, economic and social principles enumerated below:

The law guarantees women equal rights to those of men in all spheres.

Any man persecuted in virtue of his actions in favour of liberty may claim the right of asylum upon the territories of the Republic.

Each person has the duty to work and the right to employment. No person may suffer prejudice in his work or employment by virtue of his origins, opinions or beliefs.

All men may defend their rights and interests through union action and may belong to the union of their choice.

The right to strike shall be exercised within the framework of the laws governing it.

All workers shall, through the intermediary of their representatives, participate in the collective determination of their conditions of work and in the management of the work place.

All property and all enterprises that have or that may acquire the character of a public service or de facto monopoly shall become the property of society.

The Nation shall provide the individual and the family with the conditions necessary to their development.

It shall guarantee to all, notably to children, mothers and elderly workers, protection of their health, material security, rest and leisure. All people who, by virtue of their age, physical or mental condition, or economic situation, are incapable of working, shall have to the right to receive suitable means of existence from society.

The Nation proclaims the solidarity and equality of all French people in bearing the burden resulting from national calamities.

The Nation guarantees equal access for children and adults to instruction, vocational training and culture. The provision of free, public and secular education at all levels is a duty of the State.

The French Republic, faithful to its traditions, shall respect the rules of public international law. It shall undertake no war aimed at conquest, nor shall it ever employ force against the freedom of any people.

Subject to reciprocity, France shall consent to the limitations upon its sovereignty necessary to the organisation and preservation of peace.

France shall form with its overseas peoples a Union founded upon equal rights and duties, without distinction of race or religion.

The French Union shall be composed of nations and peoples who agree to pool or coordinate their resources and their efforts in order to develop their respective civilisations, increase their well-being, and ensure their security.

Faithful to its traditional mission, France desires to guide the peoples under its responsibility towards the freedom to administer themselves and to manage their own affairs democratically; eschewing all systems of colonisation founded upon arbitrary rule, it guarantees to all equal access to public office and the individual or collective exercise of the rights and freedoms proclaimed or confirmed herein.

Updated : 15 December 2022