The notions of liberty, equality and fraternity were not invented by the Revolution. Closer ties between the concepts of liberty and equality were frequent during the Enlightenment, particularly with Rousseau and Locke. However, it was not until the French Revolution that they were brought together as a tripartite motto. In a speech on organizing the national guards in December 1790, Robespierre proposed that the words “The French people” and “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” should be emblazoned on uniforms and flags, but his suggestion was not adopted.

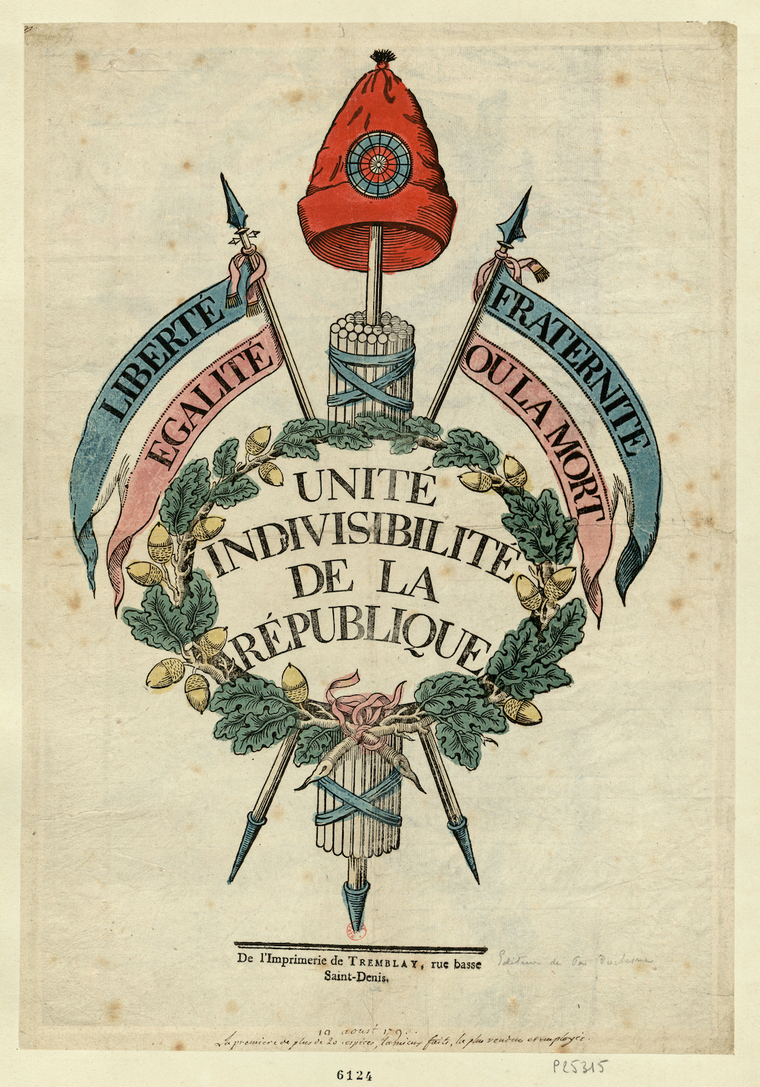

As of 1793, Parisians, quickly imitated by people from other cities, painted the front of their houses with the inscription: “Unity, indivisibility of the Republic: liberty, equality or death”. The last part of the motto, too closely associated with Reign of Terror, quickly disappeared.

Like many Revolutionary symbols, the motto became obsolete during the Empire. It returned during the Revolution in 1848, which defined it as a principle of the Republic, enshrined in its constitution. The Church then accepted this triad as a summary of Christian values: priests celebrate fraternity with Christ and bless Liberty Trees.

It was rejected during the Second Empire but finally came to the fore in the Third Republic, despite some resistance, including among Republicans: solidarity was sometimes preferred to equality, which involves social levelling, while the religious connotation of fraternity did not have unanimous support. The motto was added to the pediment of public buildings on 14 July 1880. It appears in the Constitutions of 1946 and 1958 and is today an integral part of our national heritage.

See the other symbols of the French Republic

Updated : 14 December 2022