Jean-François Delhay, Architecte des Bâtiments de France

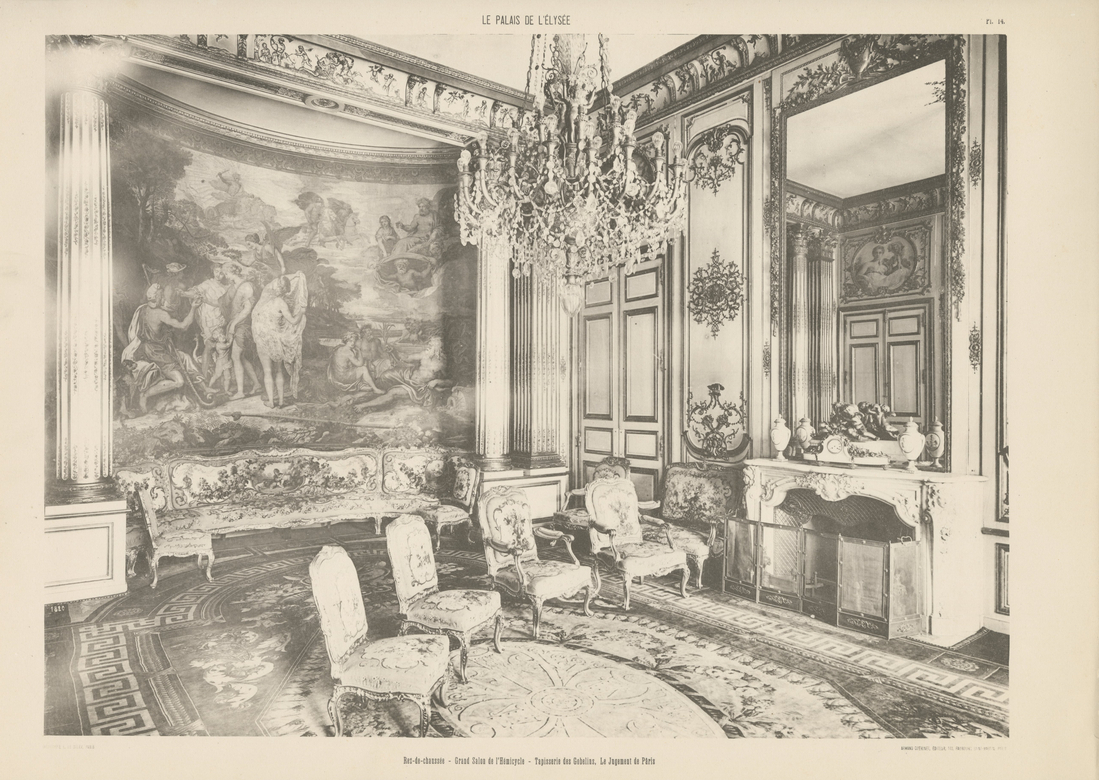

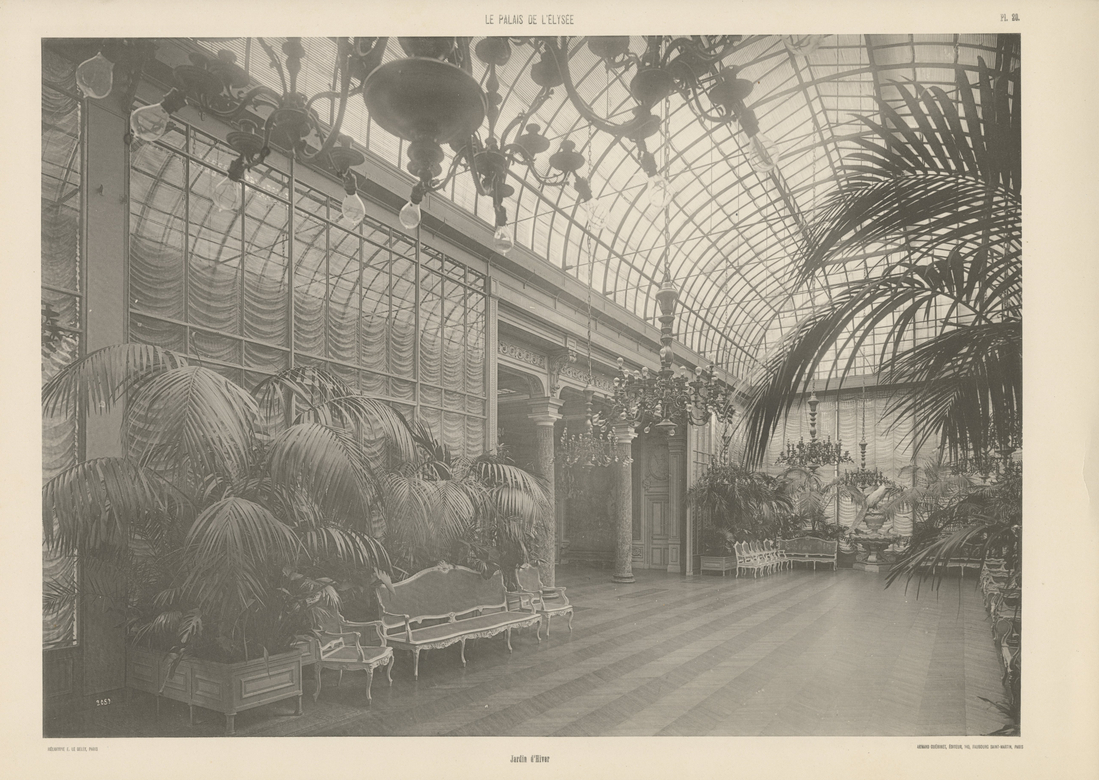

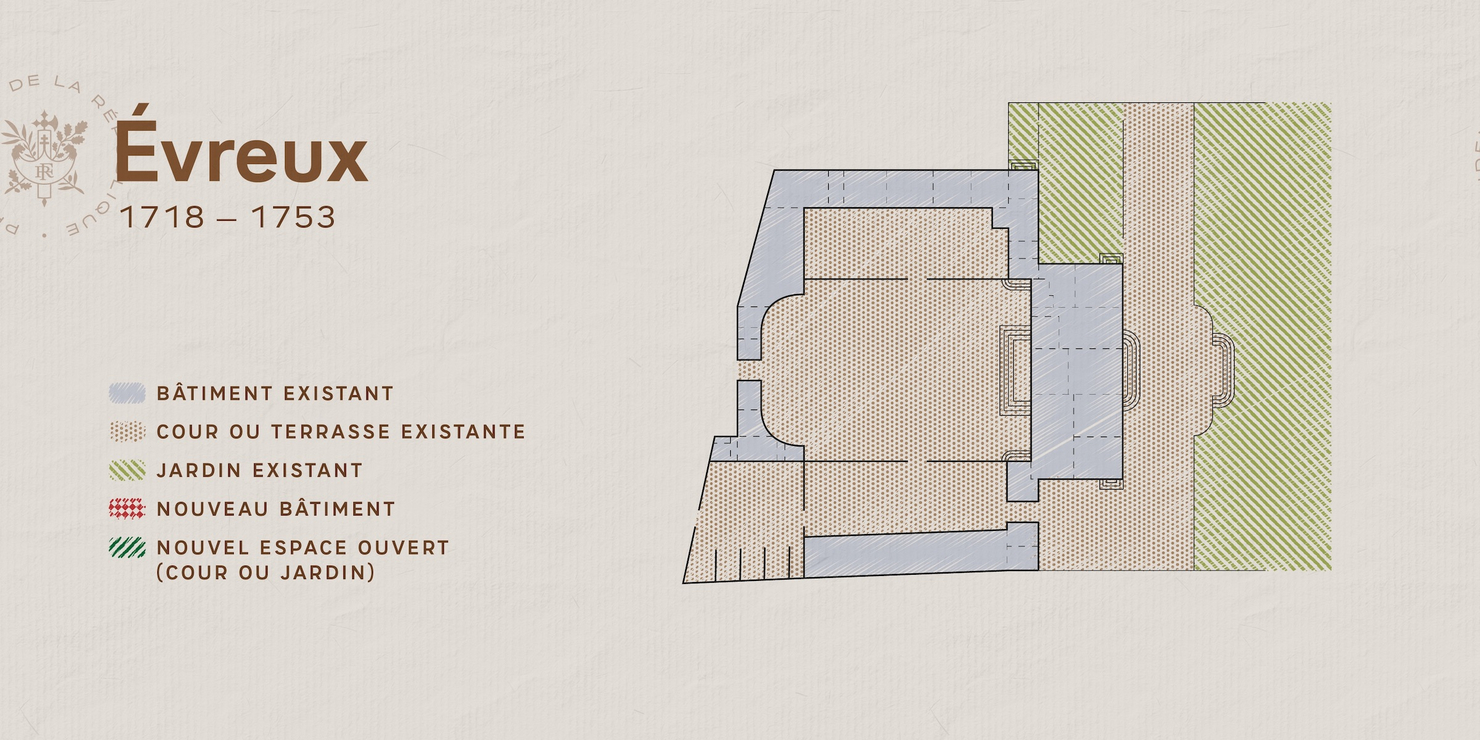

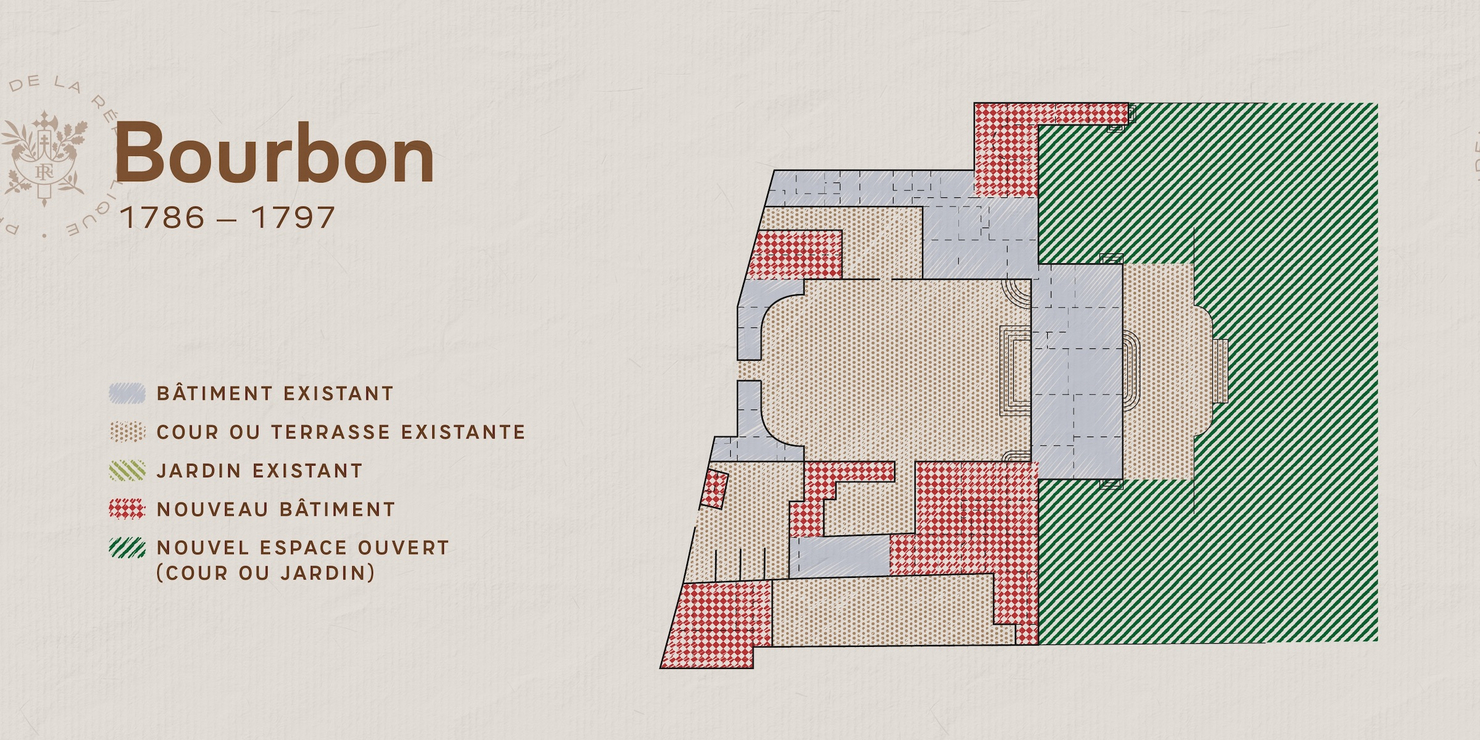

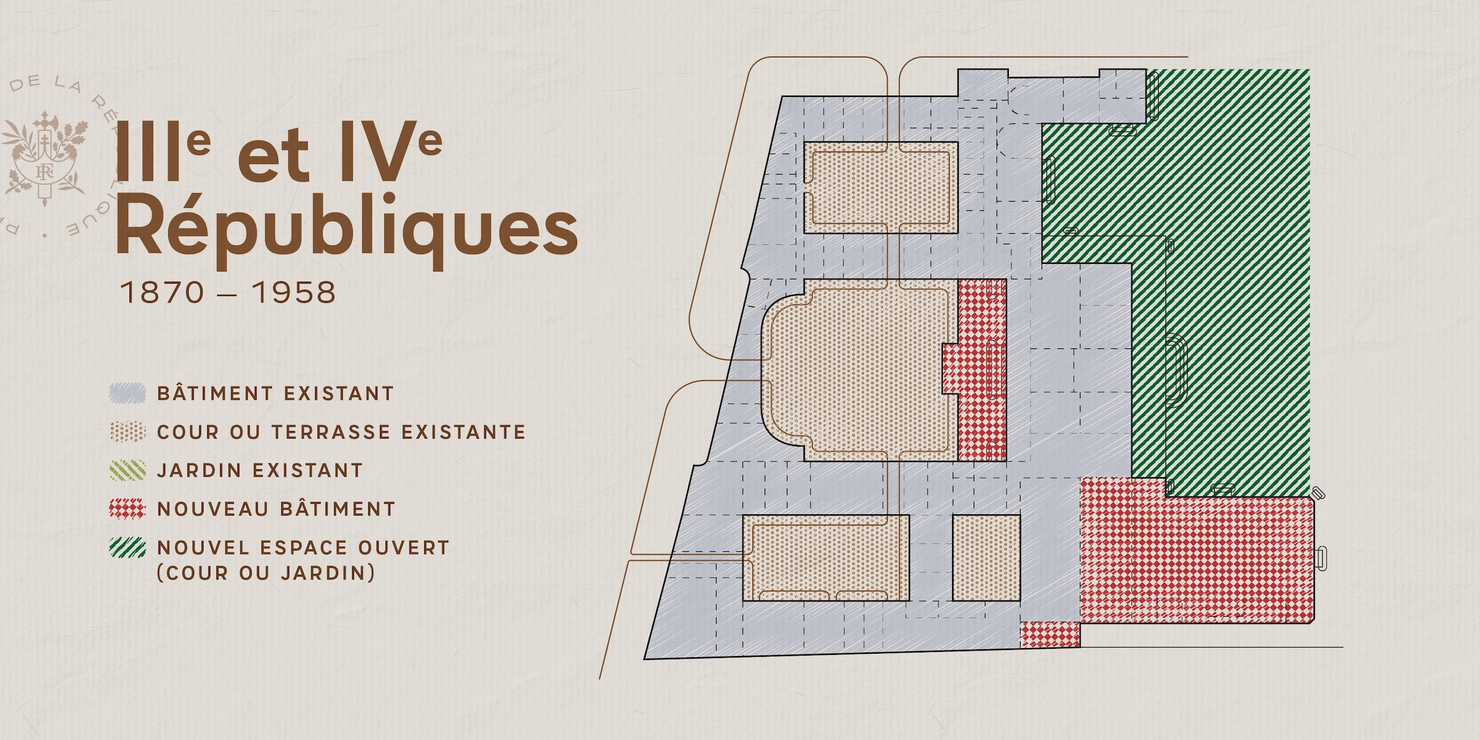

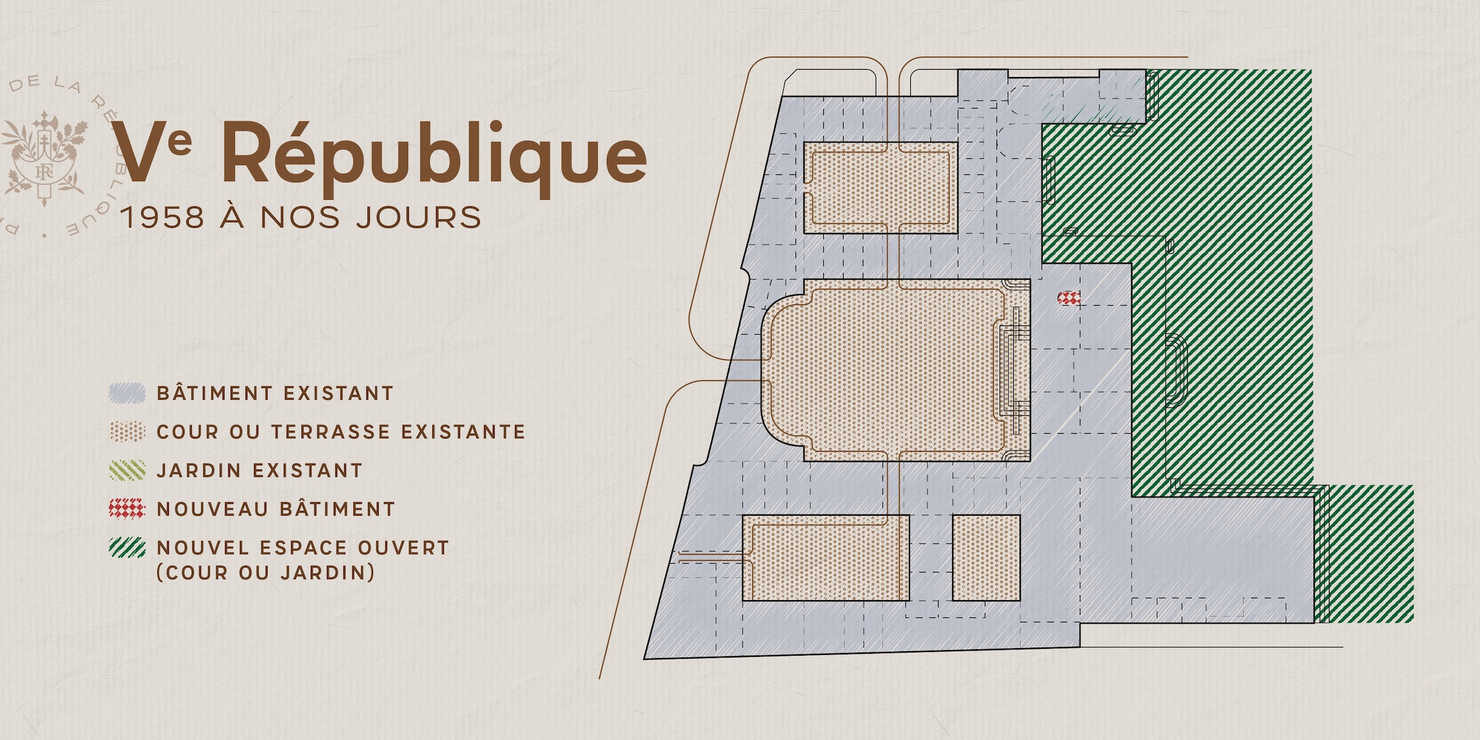

Since the palace was built in 1718, one main building has remained consistent, the Hôtel d’Evreux, which has roughly maintained its original dimensions, as well as the courtyard. The building has remained, in my opinion, quite similar. Someone who saw the building in the early 18th century would have the same impression if they came back to see it today. I think they could identify this building. Everything that makes up the annexes, the communal areas in particular, and side yards of the courtyard were closed off with simple walls with arcades, in the architectural style Pierre Lescot used for the Lescot Wing of the Louvre, which concealed the stables behind it, at the back of the courtyard. Today, there are inner courtyards with one-storey constructions built around them. So these communal areas were entirely modernized during the time of Napoleon III. So there is the section with all the main reception rooms: Napoleon III Drawing Room, Jardin d’Hiver, Salle des Fêtes, which were significant additions in the mid-19th century. There is the east wing, or the private wing, with the Salon d’Argent and the Salon Paulin, which were expanded in the late 18th century in particular, and again raised in height later on.

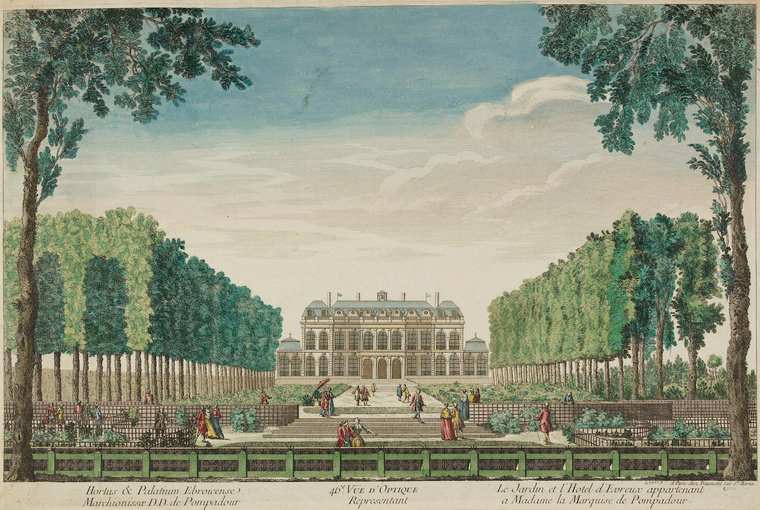

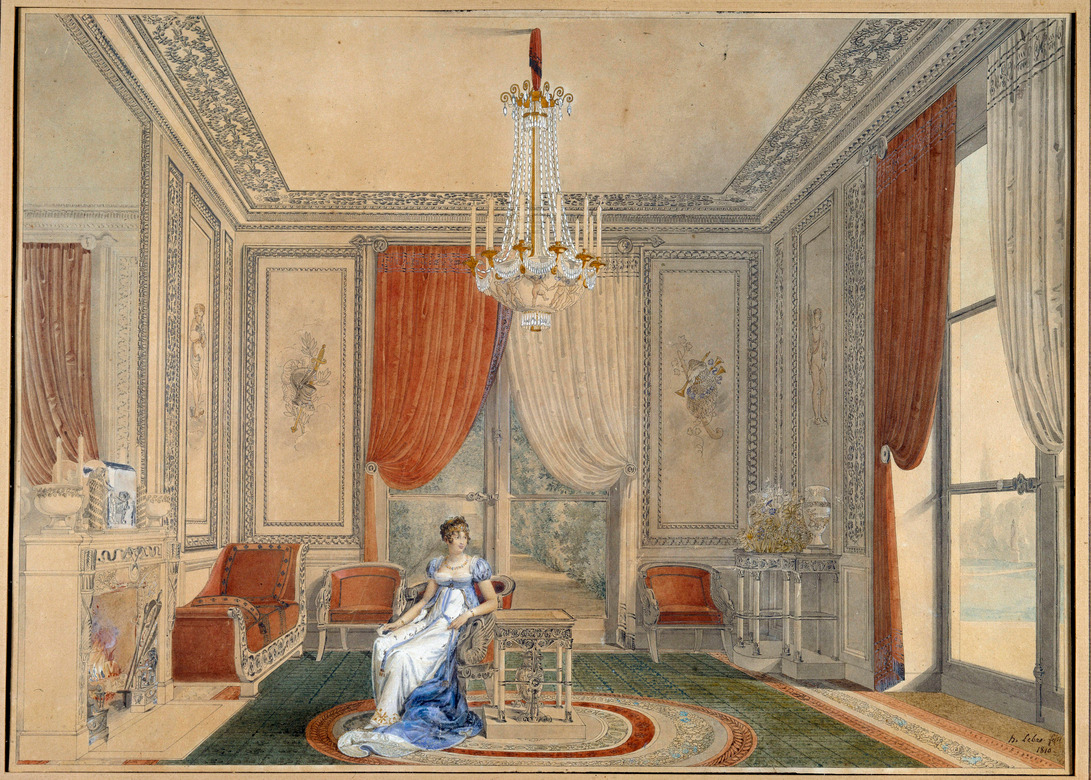

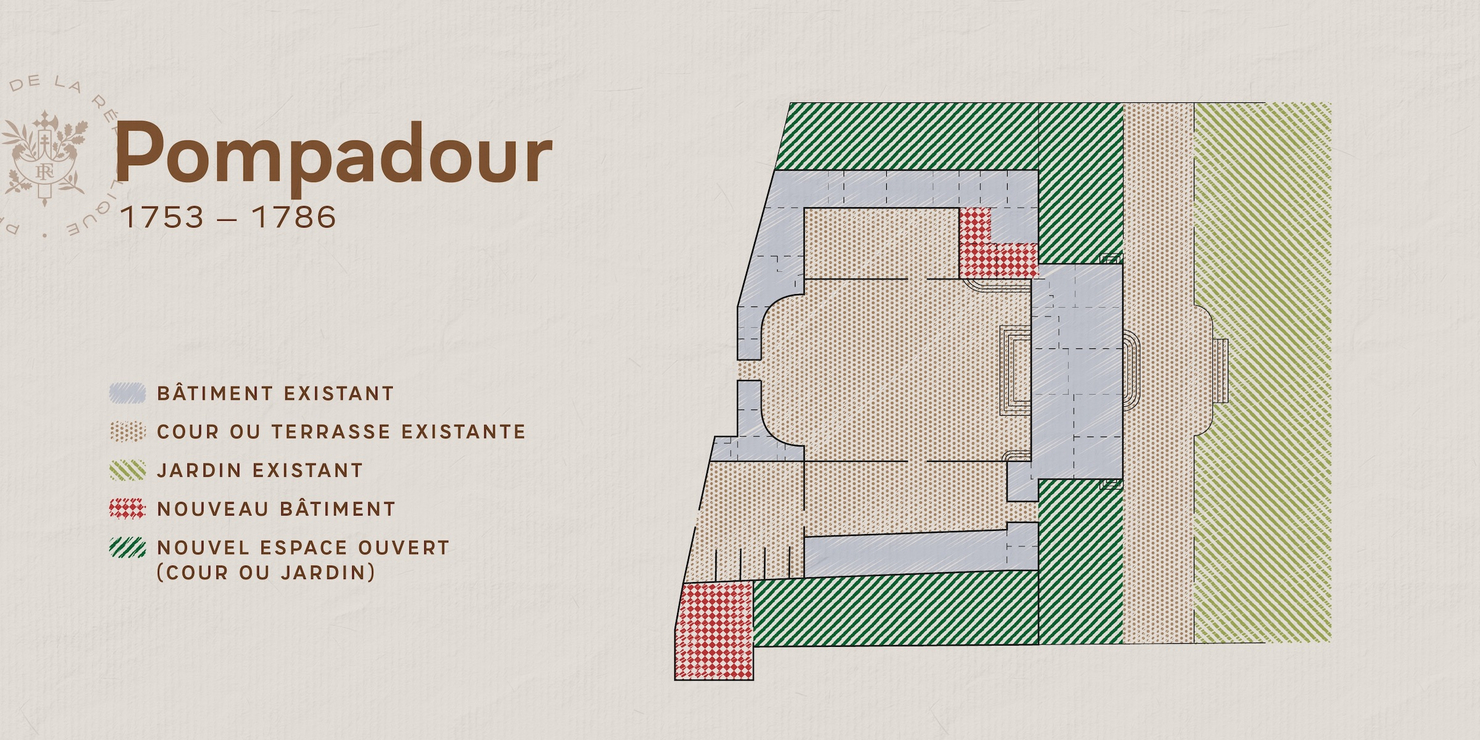

So it is really the main building that has maintained its original external dimensions from 1718. At the time, when the Count of the Tour d’Auvergne had this mansion built, he only occupied the ground floor. The upper floors, which was property lying unused, included the first floor and the attic space, which were converted later on by the Marquise de Pompadour.

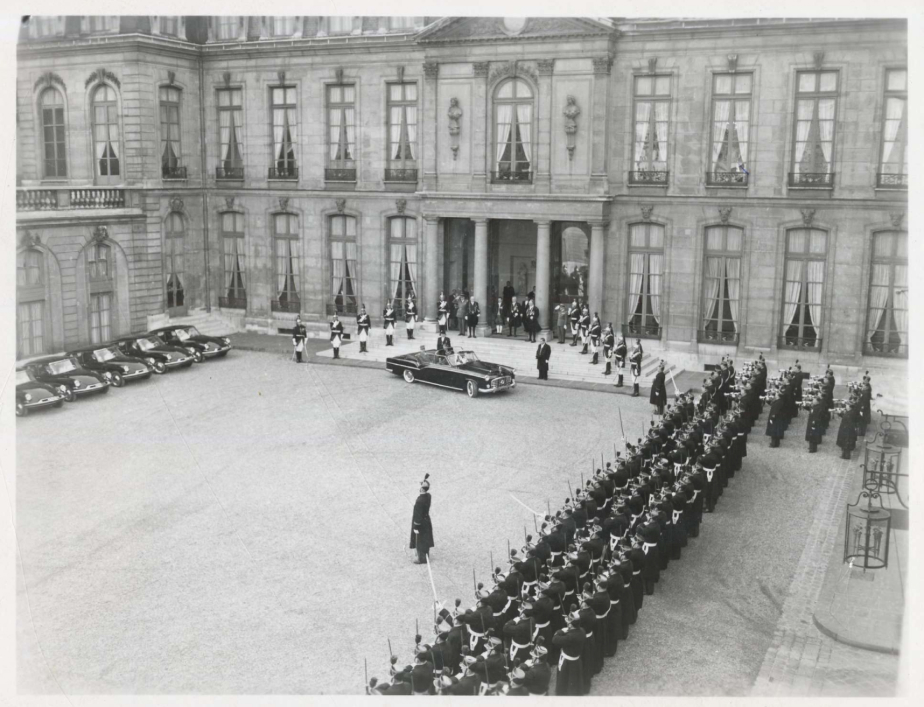

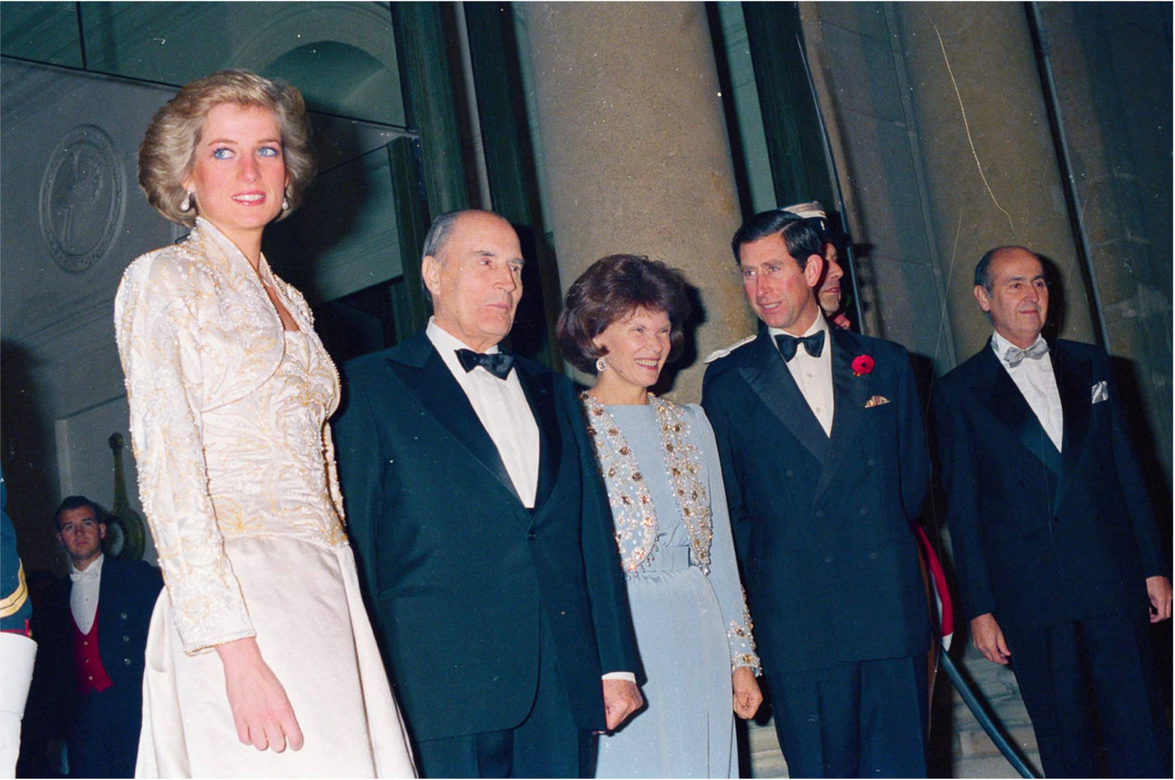

Everything was in a straight line – you could walk straight through from one end to another. When you entered the building from the central courtyard, you could see a peristyle which was totally open, and not enclosed by windows, and most importantly there was a door to what is now the Salon des Ambassadeurs. Today, all of that is closed off. When you ascend the staircase to the front door, and the president welcomes a foreign Head of State, he takes either the Murat Staircase to the left, or he can enter the Salon des Tapisseries on the right. Now, you can no longer walk straight through to the main room, and then the gardens.

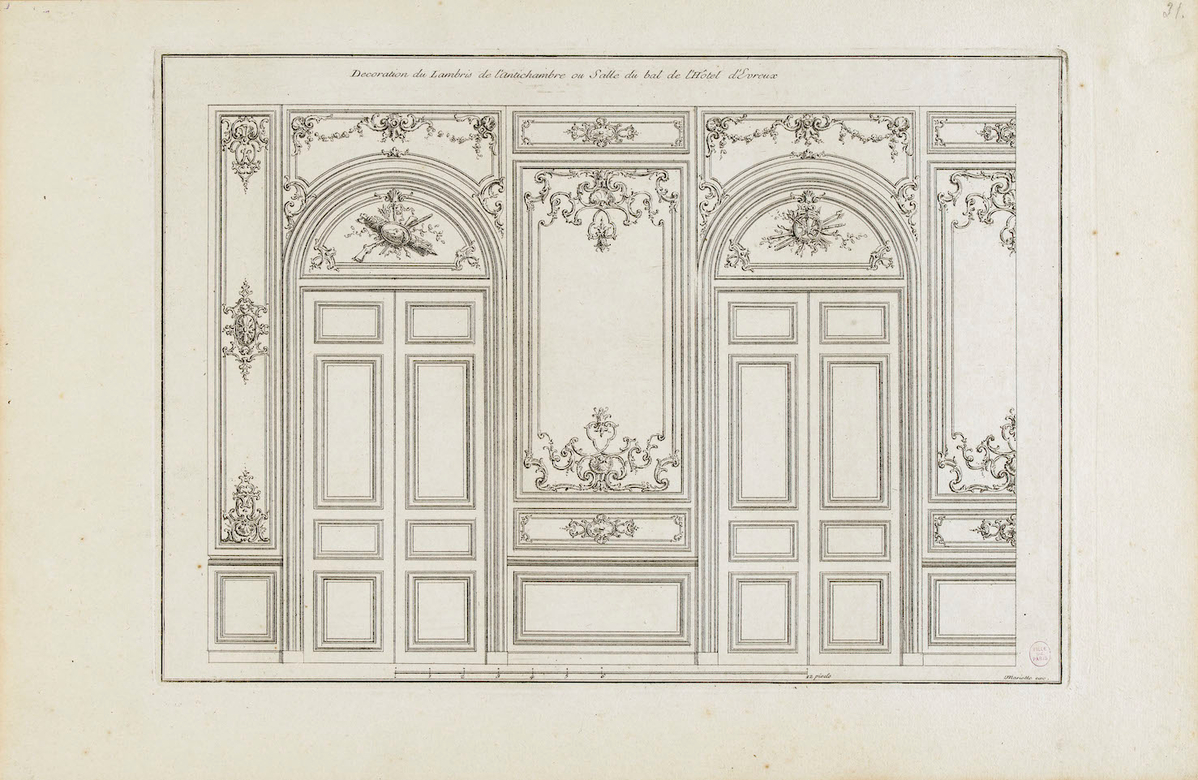

In its current state, the resident who left the strongest mark on the mansion is without question Napoleon III. Napoleon III made it a residence for a Head of State; you might say he was the first Head of State to reside there but also made it into the reception venue as a Head of State. He completely restructured the building. He replaced the wooden floors on the first floor, which were in extremely poor condition, and he had the decorative features replaced, as they were damaged. In fact, sometimes, it’s very interesting, for example, that the fireplace of the Salon Doré, which is today the office of the President of the Republic, is a copy of a fireplace in Versailles, from the Louis XVI era, I believe. So the decorative features were redone with ones already there, and copies were made of those items using stamping techniques. Of interest is that the moulding from the Salon Doré is inspired by the moulding in the Salon Pompadour on the ground floor. Napoleon III oversaw the creation of the Salon Napoleon III, he had the main kitchens installed; knocked down and rebuilt the section with the stables and communal areas, making the entire expanse of the courtyards fully urbanized, and not just the exterior façades.

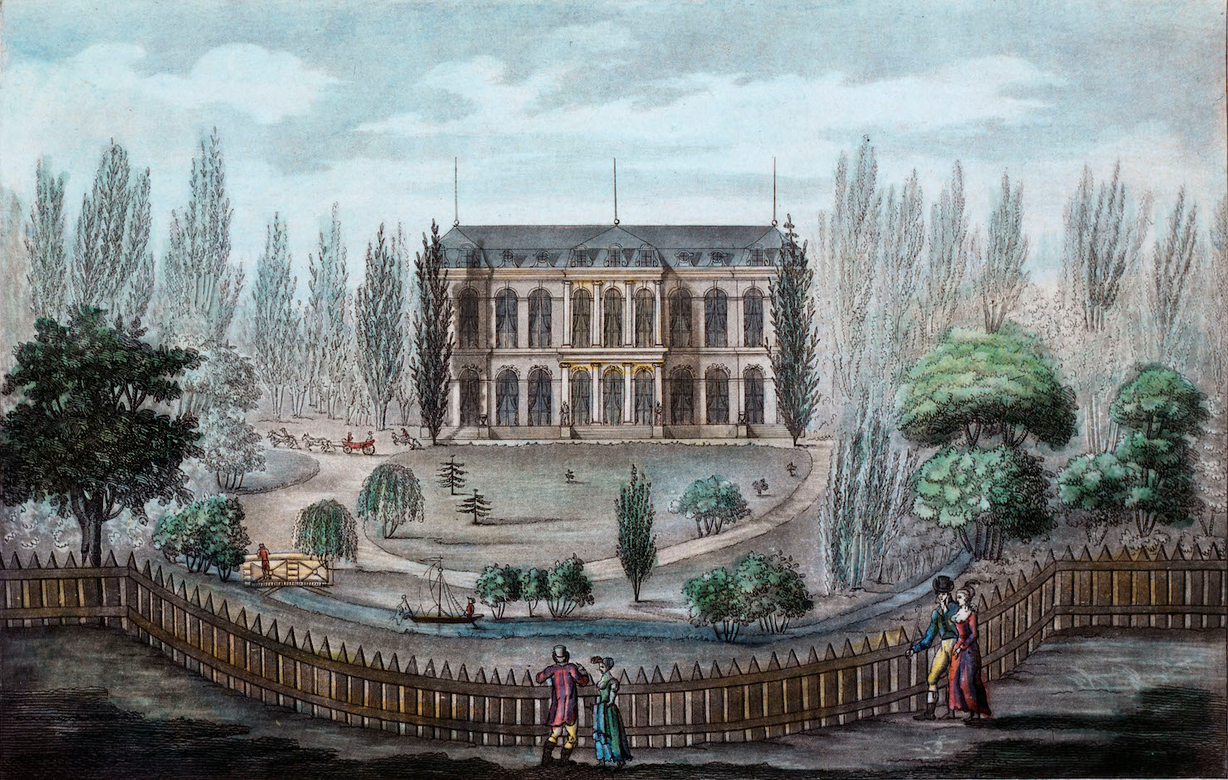

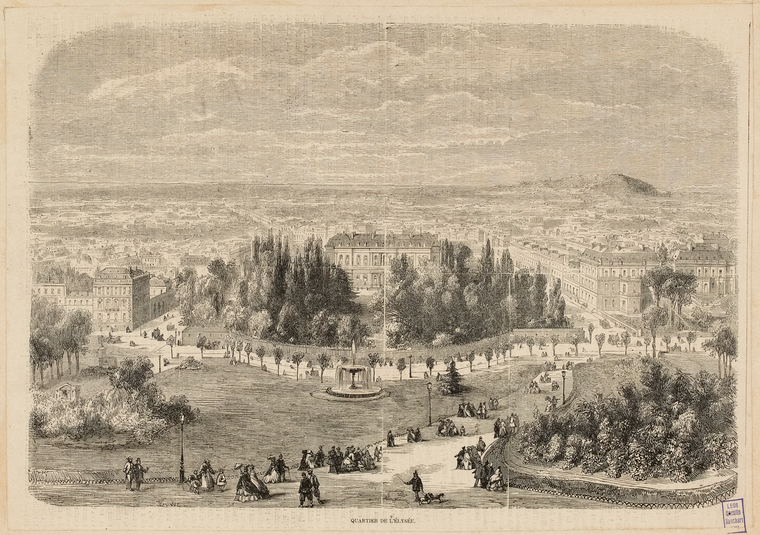

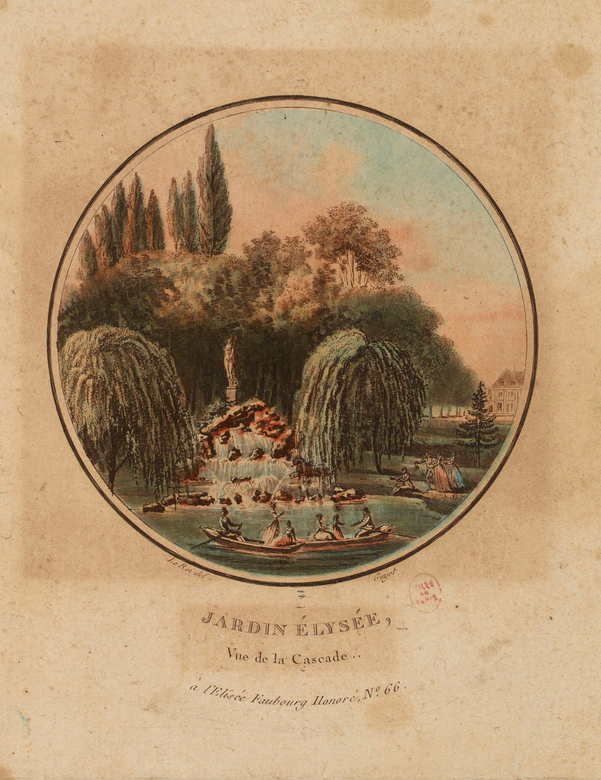

The unique thing about the Hôtel d’Evreux is that it is a good example of the architecture that developed in the early 18th century, which coincided with the urbanization of the Champs Elysées and the huge private mansions. It consists of a house that is on the street and a huge garden that backs onto the Champs Elysées. And of course, the Hôtel d’Evreux is one of the few private mansions, along with the British Embassy, the Circle of the Interallied Union, the U.S. Embassy, and the residence of the U.S. Ambassador, that still have gardens that back onto the Champs Elysées. But the Hôtel d’Evreux goes even further than the rest, as you can see, it extends out – this protrusion was obtained by Madame de Pompadour, and was in fact severely criticized at the time. So it was this huge parkland, which today is an English garden, that made it an exceptional residence.

Michel Goutal, Architecte en Chef des Monuments Historiques (historic monument architect)

In reality, it isn’t exactly a private mansion. That’s the unique aspect of the Élysée; it has one foot in the world of châteaux, the other in the world of private mansions (“hôtels particuliers”, in French). Quite simply because geographically, it had one foot in the city and the other in the countryside. You need to imagine that the Champs Élysées was a bridle path through woodlands. So when we see the layout of the original gardens, you can see the façade on the garden side, but not behind a fence – there was what was called a “ha-ha”, as it was seen as an element of surprise – then it was called a “saut-de-loup”, or sunken ditch, which meant no fence was needed. And so you could see the garden and the parkland from an almost-forested bridle path. In terms of its size, it is almost like a château. If you take the Élysée Palace and put it in the countryside, you have a beautiful château. It is a massive private mansion that was built and made by very wealthy people. So it was quite impressive, all the same. The fact that it wasn’t inside a property in the city of Paris made it more accessible in terms of developing the parklands. And even the gardens don’t look like the gardens of a private mansion. They are the size of a park in a small château. If, instead of the Champs Élysées, we had a forest all around, the garden and the little park would resemble those of a château.

In the past fifteen years, a lot of work has been done on all of the interior design. This is true of the ballroom and all of the reception rooms on the garden side of the ground floor. They have all been restored. On the upper floor, the President’s office was also restored and this summer we will focus on the Salon Vert, the lounge next to the President’s office, to do rather technical refurbishment. The floor will be redone, along with the technical shafts and some major maintenance work because this room was last restored in 2007. It will involve some alterations. All of these rooms are functional, so there are costs related to repairing chairs ...They need to be brought up to standard. However, everything in terms of flooring, which wasn’t dealt with in 2007, will be dealt with definitively. So in theory we’ll be good for 15 years.

When the landing of the main stairway (escalier d’honneur) was restored, a parquet floor was replaced by a stone floor, as it was originally. So when the parquet fillets were removed, there were fillets that had been blocked with papers that were hand-signed by Madame Auriol, so that indicated when the parquet had been redone. Madame Auriol’s signature was there, which meant it could be dated.

The memory that sticks out the most is during the 2011 renovations, when we did the courtyard, the Salon Murat, the Salon des Ambassadeurs, and the Grille du Coq, which is the entrance to the gardens. We did it all in 23 days, so that was quite extraordinary.